How happy are we? How to make hard choices

A philopsophy on how to make hard choices with Ruth Chang. A look thourgh some happiness survey data. Sustainability UnConference: London Sep 6, Chatham House Education: Peter Gray on play.

How to make hard choices

Happiness: How happy are we?

Education: Peter Gray on play

Climate: David Finnigan on when to place a climate story

Robo-taxis: China leading the way for driverless cars

Child/education: The Marshmallow test does not replicate.

I’ve been travelling and away for a while. My main recent thinking has been reflecting on happiness data and if the UK is really that unhappy (seemingly not); and a thought provoking conversation with philosopher Ruth Chang on a different way of thinking about making hard choices.

Taylor Swift or Paul McCartney? Law or Philosophy? How should we make hard choices? Ruth Chang is a prominent philosopher known for her work in decision theory, practical reason, and moral philosophy.

She is well known for her theory of "hard choices," where she argues that many choices are not determined by objective reasons but instead involve values that are incommensurable.

If Ruth is correct, it does open up a different way of thinking about moral and social choices when the decision is “hard” - as in finely balanced between different items which are hard to value. As such, I think it’s worth pondering.

The podcast discussion delves into the inadequacy of the traditional trichotomous framework—better, worse, or equal—in evaluating values and making decisions. Chang argues for recognizing 'hard choices' as situations where options are qualitatively different yet equally viable, introducing the concept of 'par'.

This idea is applied to various scenarios, from career decisions to healthcare dilemmas, and even the design of AI systems. Chang highlights the importance of human agency in making commitments when faced with hard choices, offering a framework to help individuals become the authors of their own lives.

Furthermore, Chang shares insights about her current projects aimed at rectifying fundamental misunderstandings about value in AI design, advocating for a more nuanced and human-aligned approach to machine learning.

The episode also touches on the philosophical influences of Derek Parfit and explores concepts like effective altruism, transformative experiences, and the value of commitment in living a meaningful life.

To become the author of your life, ascertain what matters, understand how alternatives relate to what matters, tally up pros and cons, and then open yourself up to the possibility of commitment. Realize yourself by making new reasons for your choices.

Transcript, podcast and video, available wherever you get podcasts.

Or below here:

Apple Podcasts: https://apple.co/3gJTSuo

Spotify: https://sptfy.com/benyeoh

All links: https://pod.link/1562738506

“I don’t care… as long as my children are happy!” I hear a refrain like that quite a bit. I was reflecting on how happy we are in general.

As I am perplexed / thoughtful on how the UK / world is doing in terms of human flourishing (I think the GDP picture can be interpreted a number of ways) I thought I’d look at survey data.

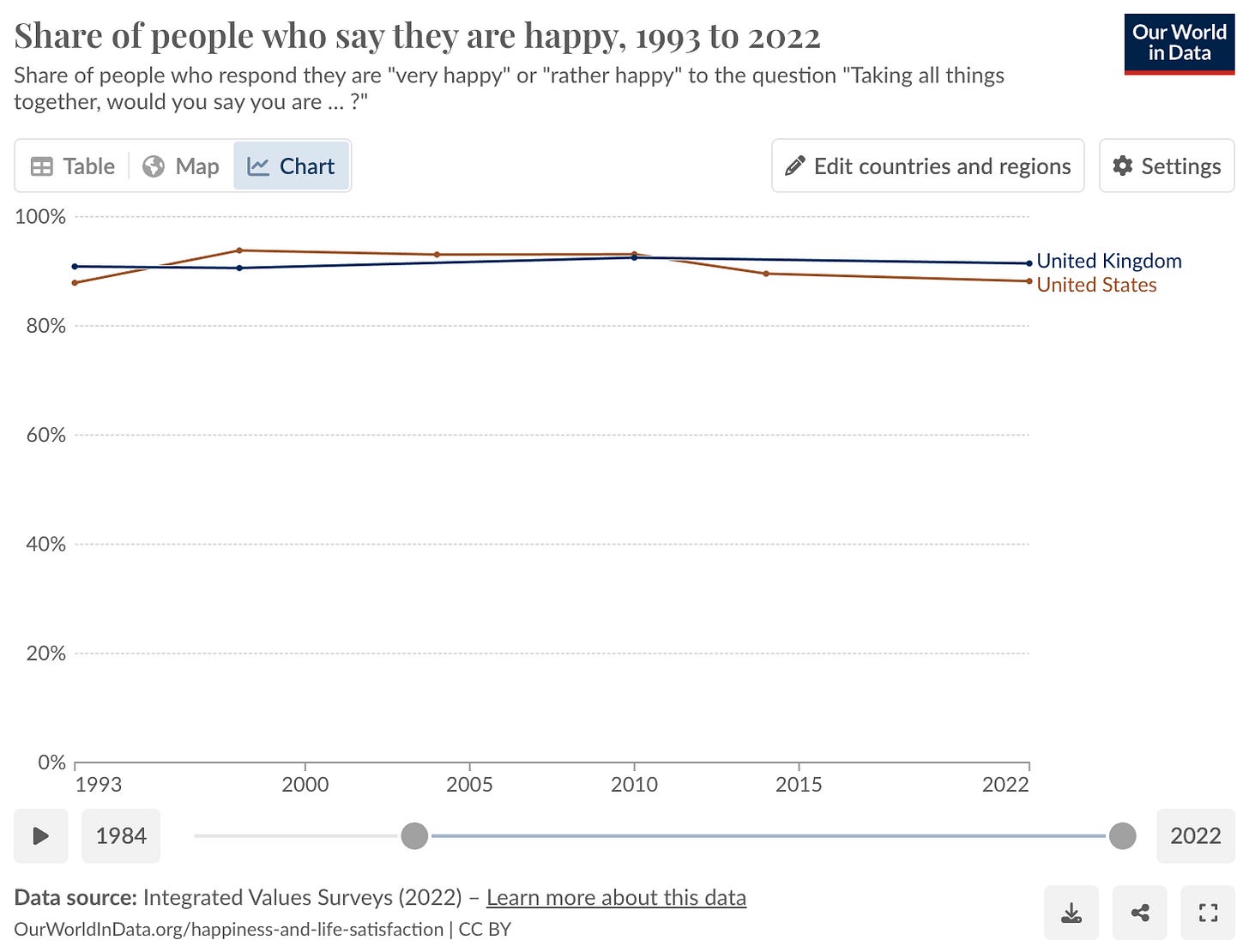

In the UK we are almost at peak happy if you look at it this way:

Although you can ask this differently and get a different cut of data:

The YouGov survey question is:

Broadly speaking, which of the following best describe your mood and/or how you have felt in the past week…?

And that is 52% respond happy (much lower number but still close to peak happiness at the moment). The long term range is pretty tight.

Perhaps more surprising to me, was the “life satisfaction question” which seems really stable to me over the last 5 years.

Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays? To be answered on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is "not at all" and 10 is "completely".

Again from YouGov: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/trackers/life-satisfaction-measured-weekly

Does this say something about our emotional homeostatic equilibrium?

Our World in Data (OWID) argue this:

Social scientists often recommend that measures of subjective well-being should augment the usual measures of economic prosperity, such as GDP per capita. (1) But how can happiness be measured? Are there reliable comparisons of happiness across time and space that can give us clues regarding what makes people declare themselves ‘happy’?

… the data reveals.

Surveys asking people about life satisfaction and happiness do measure subjective well-being with reasonable accuracy.

Life satisfaction and happiness vary widely both within and among countries. It only takes a glimpse at the data to see that people are distributed along a wide spectrum of happiness levels.

Richer people tend to say they are happier than poorer people; richer countries tend to have higher average happiness levels; and across time, most countries that have experienced sustained economic growth have seen increasing happiness levels. So, the evidence suggests that income and life satisfaction tend to go together (which still doesn’t mean they are one and the same).

Important life events such as marriage or divorce do affect our happiness but have surprisingly little long-term impact. The evidence suggests that people tend to adapt to changes.

Rather than ask about “happiness” we can ask about life satisfaction.

If you ask that the UK is at peak happy (from the last data cut off in 2017)

In any case, in a somewhat counter narrative to the doom I hear about the UK and the world (I concede there is a vast amount we need to improve), the UK is not on the face of it that unhappy. In fact we are pretty happy as a nation. (The OECD data is similar, although here on a global basis there is a small upwards trend in the score over a long period)

Now, it’s worth mentioning the seemingly common sense idea that broadly speaking the richer you are, the happier you are (but potentially with some sort of ceiling).

(OWiD) there is robust evidence of a strong correlation between income and happiness across and within countries at fixed points in time. …. while less strong, there is also a correlation between income and happiness across time. Or, put differently, as countries get richer, the population tends to report higher average life satisfaction (see below).

The OWID researchers also make this point about how it is not all about the money:

This visualization shows the relationship between self-reported sense of freedom and self-reported life satisfaction using data from the Gallup World Poll. The variable measuring life satisfaction corresponds to country-level averages of survey responses to the Cantril Ladder question (a 0-10 scale, where 10 is the highest level of life satisfaction), while the variable measuring freedom corresponds to the share of people who agree with the statement “In this country, I am satisfied with my freedom to choose what I do with my life”.16

They suggest:

To our knowledge, there are no rigorous studies exploring the causal mechanisms linking freedom and happiness. However, it seems natural to expect that self-determination and the absence of coercion are important components of what people consider a happy and meaningful life.

I link this back to thinking about our children being happy.

One important - and maybe under rated - factor is the child’s ability (or perceived ability) to be free, to make their own choices (in this children are the same as adults, I would argue counter to those who suggest adults always know best; sometimes adults do, sometimes (oftimes?) they do not). (Here I would link you to Peter Gray’s work and substack link here).

Of course life satisfaction and happiness are not quite the same, although interrelated.

I think this challenge in language concept also explains why children can impact reported “happiness” negatively yet, parents can also say it’s the best thing that happened to them.

(Less adult freedom, less sleep, less intimacy etc.)

But can improve “life satisfaction” or meaning.

The old Greeks had this with this concept Eudaimonia:

Eudaimonia (/juːdɪˈmoʊniə/; Ancient Greek: εὐδαιμονία [eu̯dai̯moníaː]), sometimes anglicized as eudaemonia or eudemonia, is a Greek word literally translating to the state or condition of 'good spirit', and which is commonly translated as 'happiness' or 'welfare'. Or…. “the flourishing life” or “the good life”. …not an emotional state or pleasure, but rather a fulfilled life, one that is lived in accord to our deepest values and aspirations not just for ourselves but for our families and community.

But they also had a type of stoic “happiness”

…life is about suffering. Happiness is to accept the obstacles with serenity….

And hedonism happiness

…happiness is spending time doing what gives you pleasure. …

And a type of epicurean happiness (which I might mistate) as:

…Happiness is the absence of suffering…

I have a few more items to reflect on here.

First, I am tentative about all this data because I think people have such different views on what “happiness” is.

Second, “positive” and “negative” words make a difference.

“These are four positive wellbeing measures—life satisfaction, enjoyment, smiling and being well-rested—and four negative well-being variables—pain, sadness, anger and worry. …we find country and state rankings differ markedly depending on whether they are ranked using positive or negative affect measures. The United States ranks lower on negative than positive affect, that is, its country wellbeing ranking looks worse using negative affect than it does when using positive affect.”

From economist Danny Blanchflower work: https://sites.dartmouth.edu/blanchflower/

Third, the averages might be misleading. Blanchflower suggests certain groups:

18 - 25 year olds

And women

May be doing particularly poorly on these happiness metrics. Although at least for young people this doesnt seem to be the case in the YouGov mood tracker.

That was my dash through reading the happiness literature. It is somewhat contested and I think the OWID data and Blanchflower work are good summaries.

As it relates to the UK, we seem much more OK than I would have thought from the “vibes” and (although this is my a priori assumption) freedom and agency seem to be important (cf Peter Gray on agency and children) along with health and wealth (as you might have expected).

(Note as a counter: this 2018 paper suggests the data not easy to replicate of flawed)

Other links:

Are you interested in exploring some of the big questions facing humanity today? Underwhelmed by traditional conference formats? Ready to get involved and help shape practical responses to some of our biggest long-term challenges?

Join Chatham House for the 2024 Sustainability Accelerator UnConference, to discuss how civil society and policymakers can accelerate towards a fair and sustainable future.

At traditional conferences, some of the best conversations happen in the corridors and the audience have just as many ideas as the panel. In Open Space events, participants manage their own agenda of parallel working sessions around a central theme. The Sustainability Accelerator Unconference aims to harness the collective power of all of its participants to bring new ideas to discussions on sustainability

David Finnigan on when to set climate stories:

Someone recently asked me my advice about writing a climate story. Their question was striking: rather than ask about content or form, they wanted to know, when should their story be set? Is climate change best discussed through narratives of the past, present or future?

It’s a question I’ve been returning to over the last few weeks, turning over and over and holding it up to the light.

and…

…although climate stories set in the present day help us to really see the world we live in, and awaken us to the choices we can make to change the future, they miss out on a key element - the context for how we got here. There’s an argument to be made that climate stories are not just future or present tense - they’re historical.

In his 2021 book The Nutmeg’s Curse, Indian writer Amitav Ghosh writes about his conversations with Bengali migrants who have fled their homes and travelled to Europe due to increased flooding, heat or environmental damage.

To me - sometimes we see things more easily through the lens of history (or even fantasy / science fiction) than we do through the lens of now.

On Robo-taxis: From Economist (H/T Adam Tooze):

Apollo Go, which launched in Wuhan in 2022 .. has since expanded to ten other Chinese cities …. Its service has carried out 6m rides nationwide since launching. It now has more than 400 driverless cars on the road in Wuhan and plans to have 1,000 running by the end of this year. Chinese carmakers including Hongqi and Arcfox make the vehicles for Baidu, which provides the technology. Most of its cars in Wuhan have “level four” autonomy, which means they do not require human intervention in most situations on the road but can get muddled in areas such as parking garages—which might explain why it asks customers to trudge through the city’s sweltering heat. The reason Apollo Go has … gained such favour with riders is that it is astonishingly cheap. Your correspondent’s 11-minute spin cost just 9.84 yuan ($1.35). Such fares are possible thanks to the largesse of Baidu, which is covering around 60% of the cost of a ride. That is not sustainable. But, thanks to plummeting costs, the company reckons its robotaxis in Wuhan will break even by the end of the year and turn a profit in 2025.

Drivers account for about half of the total cost for a conventional ride-hailing service. But an assortment of other expenses associated with autonomous vehicles—from maintenance and cleaning to sensors and, most importantly, the software on which they run—have so far prevented them being a cheaper substitute. Baidu sees that changing. In May it unveiled its sixth-generation vehicle, which costs less than half the previous model, and plans to upgrade the fleet in Wuhan. As the business has expanded the supply chain has matured and Baidu has been able to spread the cost of developing and updating its technology over more vehicle

Source: Economist

and on marshmallow test continuing to not replicate (H/T Tyler Cowen):

This study extends the analytic approach conducted by Watts et al. (2018) to examine the long-term predictive validity of delay of gratification. Participants (n = 702; 83% White, 46% male) completed the Marshmallow Test at 54 months (1995–1996) and survey measures at age 26 (2017–2018). Using a preregistered analysis, Marshmallow Test performance was not strongly predictive of adult achievement, health, or behavior. Although modest bivariate associations were detected with educational attainment (r = .17) and body mass index (r = −.17), almost all regression-adjusted coefficients were nonsignificant. No clear pattern of moderation was detected between delay of gratification and either socioeconomic status or sex. Results indicate that Marshmallow Test performance does not reliably predict adult outcomes.