Against Education, hair removal

Case Against Education. Trust: Why is Trust lower (Alice Evans) Autism: Books, Joanne Limburg. Climate: Stripe Fellowships. Art: Doom/hope in making art. Rachel Cusk, meditations on hair.

Education: 100 years of schooling (Julia Turcaninova). Complex, against state education.

Education: Scott Alexander on Case Against Education

Trust: Why is Trust lower (Alice Evans)

Autism: Books, Joanne Limburg

Climate: Stripe Fellowships, carbon removal

Art: Doom/hope in making (climate) art, David Finnigan

Art: Rachel Cusk, women-led writing; meditations on hair removal

Climate: AI less carbon intense than writers (?), H/T Tyler Cowen, Jim Pethokoukis

Why do children read less for pleasure (H/T Henry Oliver)

Links: Climate jobs, GOAT audio book, Soumaya Keynes and Jason Furman

I’m hearing increased disgruntledness over state education. From right, libertarian leaning ideas - freedom to choose subjects not state-sanctioned; and also from left leaning ideas: freedom for children to choose, curiosity; rights of the child.

Educationalist and teacher, Julia Turcaninova has examined this from a history of education ideas perspective. Already available in Russian, the English substack translation is coming out. First part is here.

“... It appears as if there was an implicit, but universally understood, agreement between society and the state regarding the education of children, which either was suddenly terminated or simply became hopelessly outdated and ceased to be effective.

This agreement was forged at a time when the state was still perceived by the population as the boss, the master, a sort of "father figure" who knows best. A century has passed since then. The state's inefficiency as a manager has become glaringly evident to almost everyone; distrust toward it in all its forms and manifestations is growing universally, while the bloated bureaucracy is loathed by all except those directly involved in it, who are bought off by stable employment, decent salaries, and the promise of retirement benefits.

Without delving into the minor details of various countries' particular cases, it seems this agreement was based on the premise that the population entrusts their children to the state for a certain number of hours per day, for a certain number of days a year, and goes off to work. In return, the state, since it claims to know what is best for these children, promises firstly to fulfill this obligation and secondly to return the children home safely every day…”

I think it’s worth following up on the ideas.

And for bio context, this is her:

“I have met, perhaps, tens of thousands of people of all ages, educational backgrounds, experiences, and occupations. For various reasons and on various occasions, sometimes for a long time, more often for a year or two, I entered the lives of my students. I wholeheartedly tried to teach them all, and some of them, indeed, learned from me - all different things. Like every teacher, I have many hundreds of children and students behind me, whose faces or names I cannot remember: they diligently did the things connected with me, did not cause unnecessary trouble, but we never had a chance to touch souls. Why did it happen this way? One or two from almost every group of students became lifelong friends. Why them in particular? In almost every such group there were children in whom I invested like in no other, most of them went into adulthood without even looking back, and I think I understand why.

From all these experiences, meetings, reading, work, and reflections, this book was born.”

Scott Alexander - blogger extraordinaire, leans rationalist - has this recently:

“There’s been renewed debate around Bryan Caplan’s The Case Against Education recently, so I want to discuss one way I think about this question.

Education isn’t just about facts. But it’s partly about facts. Facts are easy to measure, and they’re a useful signpost for deeper understanding…”

Which rounds out some of the debate I’m reading on the alternative education ideas. We had our own UnConference on this recently (notes still coming).

On trust: Alice Evans (economic and ideas intellectual, excellent on the complexities of gender) has this on trust. Though she looks at reported trust. What’s causing trust decline…

“...Through my global-historical comparative research, I suggest several likely mechanisms:

Generalised distrust is correlated with strong family bonds

Poorer countries have rapidly urbanised at a lower level of income

Rule of law varies worldwide

Political contestation and growing polarisation

Online connectivity has boomed, and is increasingly negative..”

Culture is the first point of global variation. Strong family ties seem to be a substitute for generalised trust. A wealth of research suggests that the two are negatively correlated: one either trusts family or wider society. Scandinavia is characterised by weak family bonds and high generalised trust, whereas India has strong family bonds and low generalised trust.

Poorer countries have rapidly urbanised at a lower level of income. Cash-strapped municipalities now struggle to provide rule of law and effective services. City-dwellers are thus surrounded by diverse multitudes whom they are disposed to distrust.

Weak rule of law enables impunity for violence and exploitation. If one suspects thieves, tricksters, or sexual harassment, then cities are incredibly stressful. And where criminal street gangs murder with impunity, there is every reason for trepidation. Abuse runs rampant, wolves howl in the shadows.

Political movements vilify their foes. Group competitions are zero sum: all sides compete for supporters’ investment and loyalty. Enemies are figuratively tarred and feathered, derided as demons. In this respect, U.S. political fundraisers have much in common with Uzbekistan’s YouTube imams: hyping up external threats, while offering themselves as saviours. Political polarisation is growing worldwide.

Online connectivity is another major global trend, increasingly characterised by negativity, out-group animosity and moral outrage.

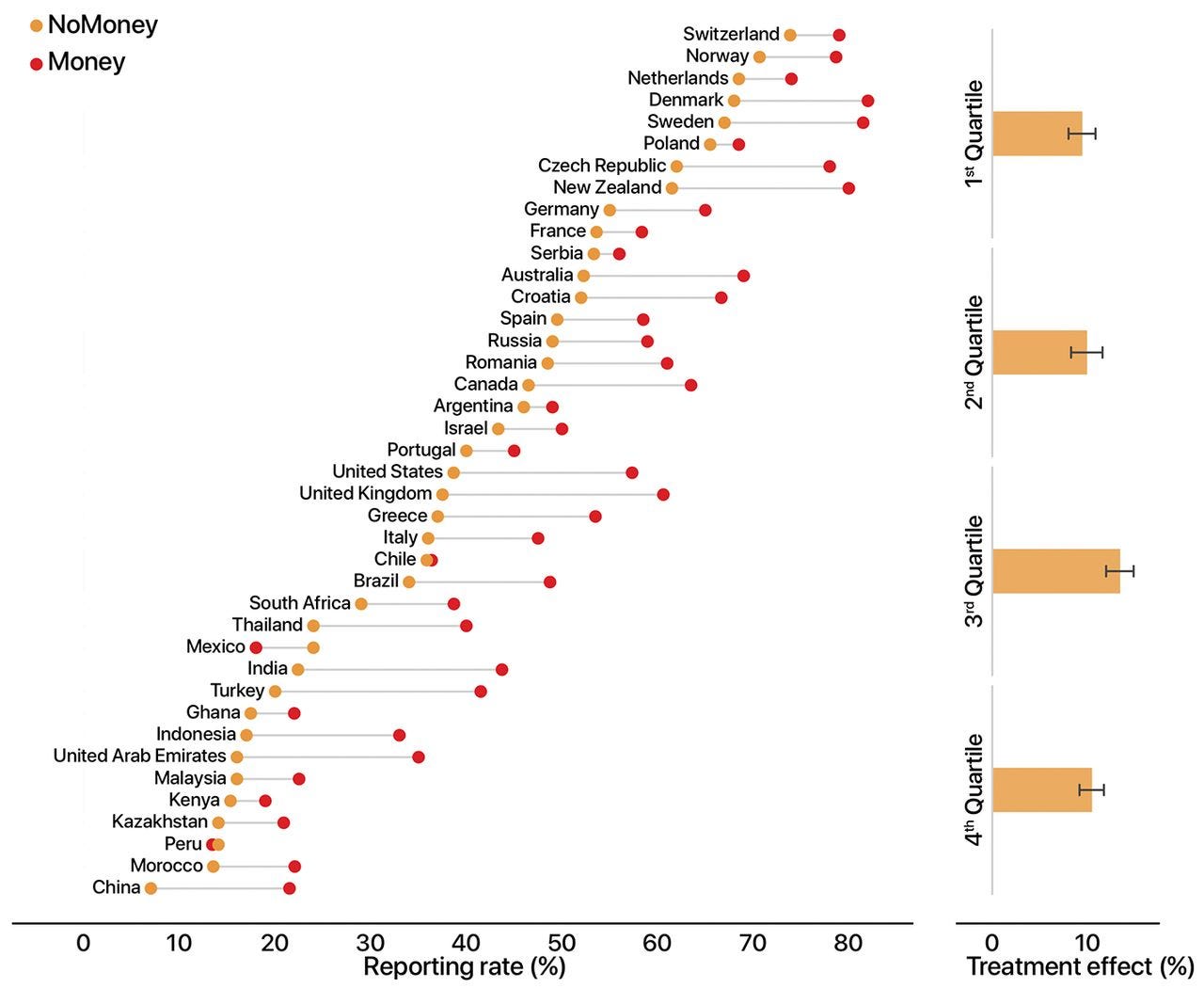

I think it’s also intriguing to look at revealed trust, which you can via this experiment on leaving wallets with money in them.

Most experts (economist in this case, but not all, with a good 3/10 being right) predicted that it was more likely that wallets with no money would be returned vs wallets with some money in them.

The results across almost every country are that it’s much more likely that wallets are returned if they had money in them.

This highlights that we are typically not good at predicting human behavior (although it seems some of us can). I expect the real life data is also very different to how we would respond in a survey. Blog on this here.

I was asked for some books on the autist experience. It struck me that this topic is now so wide ranging that it defies a genre to a large extent. I would say there is an “other” experience but that’s true of many types of experience. In any case I noted:

And,

Tyler Cowen’s Infovore

Kamran Nazeer (pen name): Send in the Idiots

Temple Grandin’s books

Naoki Higashida’s The Reason I Jump (trans David Mitchell)

as a range of experiences.

(I note Higashida’s book has been critiqued for authenticity, but on viewing the video footage, I feel fairly convinced.)

The range of experience here is varied and large. Some further works on neurodiversity by authors who are gender queer / women: Hannah Gadsby (Ten Steps to Nanette), Clara Törnvall’s The Autists: Women on the Spectrum; Donna Williams (Nobody Nowhere), Laura Williams (Odd Girl Out).

There is plenty more and this niche is still under rated vs typical memoir.

Riffing on memoir and women. Rachel Cusk has a new book out: Parade. Cusk’s writing has been part of a movement of writing by and about women. I say movement - and while identity politics does touch this area - I would suggest it is better viewed as women writing about their experience and a society that is more willing (from a very low base) to hear them.

Whether that is simply part of the gate keeping / publishing process changing or increase in recognition of women’s rights in the last 100 to 200 years or other factors it’s hard to say.

I’ve been reading more of this work over the years, in truth, simply led by what my wife reads. When I was in my teen years, I think for women writers I was particularly struck by Susan Sontag, and Sylvia Plath, and Caryl Churchill for play writing. I noticed a somewhat lack of the female lens but did not fully consider it.

I read some of the new Cusk in an extract in the FT. (I note Cusk divides people; Kate Kellaway has a positive review (“brilliant and unsettling”) in the Guardian, Johanna Thomas-Carr has a negative review in the Times (“like walking over shards of glass”).

“…She had worked in a bar and barely managed to feed and wash herself. No one had ever taught her how to treat herself with care. The other people who lived like that were all boys. She never met a girl who didn’t wash her hair and put on clean clothes and remove her make-up before getting into bed…”

I was struck by a reflection on hair (how women shave it and style it, men to some extent too: body builders, swimmers, cyclists). Given hair (a lot of it or a lack of it) doesn’t bother me too much on personal level, I’ve always been intrigued by other’s reaction to it.

I had some thoughts on when I lost my head hair here. And in particular, the difficulties black women face in reaction to their hair.

Solange Knowles has Dont’ Touch My Hair as a musical expression of some of these challenges.

Don't touch my hair

When it's the feelings I wear

Don't touch my soul

When it's the rhythm I know

Don't touch my crown

They say the vision I've found

Don't touch what's there

When it's the feelings I wear

I was going out with a girl, in my young days, who didn’t shave. It meant not much to me. Unbothered having very much grown up in the “It’s your body” school of thought. But the reaction from others was fascinating ranging from moderate to strong, and across all types of people. Women who viewed it as a strike against the patriarchy, and women who viewed it as opposite. Men who were seemingly repulsed to men who took it as a form of challenge. There were periods of time where I could see it was exhausting because it seemed to react so much against the prevailing winds of the world. Having hair was a constant social-politcal act.

There is quite a lot of this which is like the blue/pink colour preference. Pink wasn’t really a girl’s colour until relatively recently. Retail marketing and culture has a lot to answer for here.

My very traditional, very old, very elite boys school has pink as its colour because in those old elite days pink was very much a boys colour. Royalty also dressed in pink - perhaps only a diluted blood colour. The butlers of the Bank of England still dress in fancy pink tailoring.

I asked ChatGPT about this and GPT suggests hair removal goes back to Egyptian times - took a pause for a long time in the 1000s - before - a bit like the colour pink it comes back.

Historical Timeline

Ancient Practices:

Egyptians: As early as 3000 BCE, ancient Egyptian women used pumice stones and early forms of razors to remove body hair, including leg hair.

Romans and Greeks: Body hair removal was common among women in ancient Rome and Greece, often associated with hygiene and aesthetics.

Middle Ages to Early 20th Century:

Medieval and Renaissance Europe: Hair removal was not widely practiced. Cultural and religious attitudes often promoted modesty, and body hair was generally not a significant concern.

Early 20th Century:

1910s-1920s: The modern trend of women shaving their legs began to gain popularity in the West. The sleeveless and shorter dresses of the 1920s made leg and underarm hair more visible, prompting more women to start shaving.

Advertising: Companies like Gillette started targeting women with specific razors and marketing campaigns. In 1915, Gillette introduced the Milady Décolletée, the first razor marketed specifically to women.

Influence of Media: Fashion magazines and advertisements began to portray hairless legs as the feminine ideal.

Mid 20th Century:

1950s: The post-World War II era saw an increase in consumerism and beauty standards. Hollywood and fashion continued to influence the trend, with actresses and models often depicted with smooth, hairless legs.

1960s-1970s: The women's liberation movement brought diverse views on body hair. Some women embraced natural body hair as a form of rebellion against traditional beauty standards.

Late 20th Century to Present:

1990s-Present: The beauty industry expanded globally, and hair removal became a routine part of many women's grooming practices. Technological advancements introduced more methods, such as waxing, laser hair removal, and depilatory creams.

Global Influence: Western beauty standards, propagated by media and the fashion industry, influenced body hair removal practices in many parts of the world.

Social and Cultural Factors

Beauty Standards:

Smooth, hairless skin is often associated with femininity and attractiveness in many cultures. Media, advertising, and celebrity endorsements have reinforced this standard.

Hygiene:

Hair removal is sometimes linked to cleanliness and personal hygiene, though this perception varies by culture and individual preference.

Fashion Trends:

Clothing styles that expose more skin, such as swimsuits, shorts, and skirts, have increased the visibility of body hair and the desire to remove it.

Peer Pressure and Social Norms:

Societal expectations and peer pressure can influence women to conform to hair removal practices to avoid negative judgment or to fit in with prevailing norms.

Economic Factors:

The beauty and grooming industry is a significant economic force, promoting and profiting from hair removal products and services.

Gender Norms:

Traditional gender roles often dictate different grooming standards for men and women, with women being expected to maintain hairless skin as a marker of femininity.

And on Pink:

Pre-20th Century:

Renaissance to 19th Century: During this period, colors were not gender-specific. Both men and women wore a variety of colors, including pink. Pink was often seen as a variation of red, which symbolized strength and masculinity.

Early 20th Century:

1910s-1920s: Early 20th-century fashion began to show a slight preference for color-coding in children's clothing. However, the associations were not yet fixed. In fact, a 1918 article from the trade publication "Earnshaw's Infants' Department" suggested that pink was more suitable for boys because it was a stronger color, while blue was more appropriate for girls because it was more delicate and dainty.

My only clear memory of hair / lack of hair playing into my social identity, albeit transiently (apart from at times being known for somewhat crazy head hair mostly due to lack of concern about such things) was dancing in my youth. I have hardly any leg hair naturally. I was dancing with a newly-met girl on an English summer night with no particular intent except to enjoy the moments.

After a few songs I do not recall, she leaned into me and said.

I wish you were a girl. Then I’d bring you back to mine.

It was something to do with my legs. I think for a moment I had some reversed identity derived from the attractiveness of my smooth skin. The moment flew away like the notes from the song.

My friend David Finnigan who has argued that all art is a form of climate art in the age of the anthropecene has a blog about how it matters not if art is hope-ster or doom-ster.

Art can be explicitly political or by its act of being and observed can be make politic.

Good art - I guess - comes from the artist and the viewer and I also think it matters not if it is hopester or doomster. Who really knows how we connect.

Perhaps it’s like a song and a dance on a summer’s night party.

This paper (HT Tyler Cowen) suggests AI is not that carbon intense vs human writers, but probably falls under a Jevons law circumstance where as its cost falls we use more of it (think candles → light bulbs). Though the assumptions used could reasonably vary widely.

Our findings reveal that AI systems emit between 130 and 1500 times less CO2e per page of text generated compared to human writers, while AI illustration systems emit between 310 and 2900 times less CO2e per image than their human counterparts.

Cowen: “That is from a recent Nature paper by Tomlinson, Black, Patterson, and Torrance on the carbon-friendliness of AI. On one hand this is reassuring, though of course it should be noted that the carbon-emitting potential of AI largely comes from the additional economic activity (and querying activity) it may enable. So perhaps we can think of this as another example of Jevon’s Law, namely that the energy-saving technology in the longer run also increases the demand for energy, thus taking back some or all of the initially earned conservation.”

I’m still reflecting on how much AI can possible help speed up transition and low-cost energy ideas as opposed to all the other low grade things AI can do.

This (H/T Henry Oliver) is on why children might read less for pleasure (Virgina Postrel). Postrel suggests that recommendation chains have broken.

I think it’s likely that in part it is due to increased competition for “leisure time” by video games, online content and other forms of non-reading leisure activities. I recall Netflix arguing it’s competing for the amount of leisure time people have.

If you have a spare hour on average now vs the non-video game era, some of that is going to be taken up with playing Animal Crossing with friends. This is also a good argument for limited-to-zero homework, especially in the younger years. It should be noted, too, that reading itself is a more diverse activity with the availability of online fan fiction and audio books.

There is still a peer pressure effect which is a bit like a recommendation chain. If all your friends have read Harry Potter, it’s going to be weird that you haven’t.

Links:

Stripe has a climate fellowship open. Looks great if you are working in carbon removal. (mid July deadline)

Sophie Purdom’s Climate Tech VC / Kim Zhou is looking for people. NYC or London.

https://app.dover.io/dover/careers/ccd80c9d-75ee-446e-8aaf-47b07e00d07e

Econ: Soumaya Keynes has a podcast with Jason Furman

Tyler Cowen’s GOAT book now in free audiobook format (read by AI Tyler?!)